Kilifi-based Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) is making testing of coronavirus more available in the coastal region as part of public health response to control the viral disease.

Researchers at the KEMRI Wellcome Trust in Kilifi, have developed an immunological assay- a tool that detects virus footprints or antibodies on patients to track the number of people who been exposed to COVID-19 in the local population.

Immunological assays are a biochemical test that measures the presence and concentration of a macromolecule or a small molecule in a solution through the use of an antibody or an antigen.

The move, according to researchers, is part of Kemri’s COVID-19 response aimed at helping in understanding the way the novel virus behaves in various populations.

The researchers are tracking the antibodies through a process called Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay, which according to virologists, is able to detect antibody response on a COVID-19 patient who has stayed with the virus for long and the viral load has started to reduce.

According to Prof George Warimwe, a virologist and principal investigator at the institute, the process is able to tell the number of persons in a particular population, who had a previous exposure to the virus by detecting the footprints in their bodies.

“If you go to a place let’s say Kilifi, you can be able to tell how many individuals had previous exposure to the virus. This method picks up the exposure of the history of individuals who are much advanced in the infection cycle. So if you are infected today and I use that assay to work out whether you have been previously exposed, it might not give positive results because the body needs some time to respond and that is why the PCR assay works very well,” said Warimwe.

The approach, the virologist says is based on the research experience at the 30-year-old Kilifi based research institute which has previously been involved in a variety of other coronaviruses.

“This is important because it is a way of learning how to fight infections, we are doing lots of infection control measures like wearing masks, washing hands and social distancing but most importantly we need to understand how the virus behaves in this population,” he said.

Prof. Warimwe said, “There is lots of data from other parts of the world where infected people are asymptomatic (non-ill) and we don’t know how the immune response, for instance, is like for those who are asymptomatic to those who have mild disease, those who have severe disease and those who succumb to infection.”

The above questions, he said, “we can start asking them,” once we have a good data set of the relevant population in Kenya.

“This sort of information is important in the overall response. We need to understand how the disease actually affects the population because we can’t assume that the way the disease behaves in the local population is similar to how it behaves in a place like Angola for example or any other country,” explains the virologist.

He said molecular tests can only help diagnose current cases of COVID-19 and thus cannot tell whether someone has had the infection and since recovered.

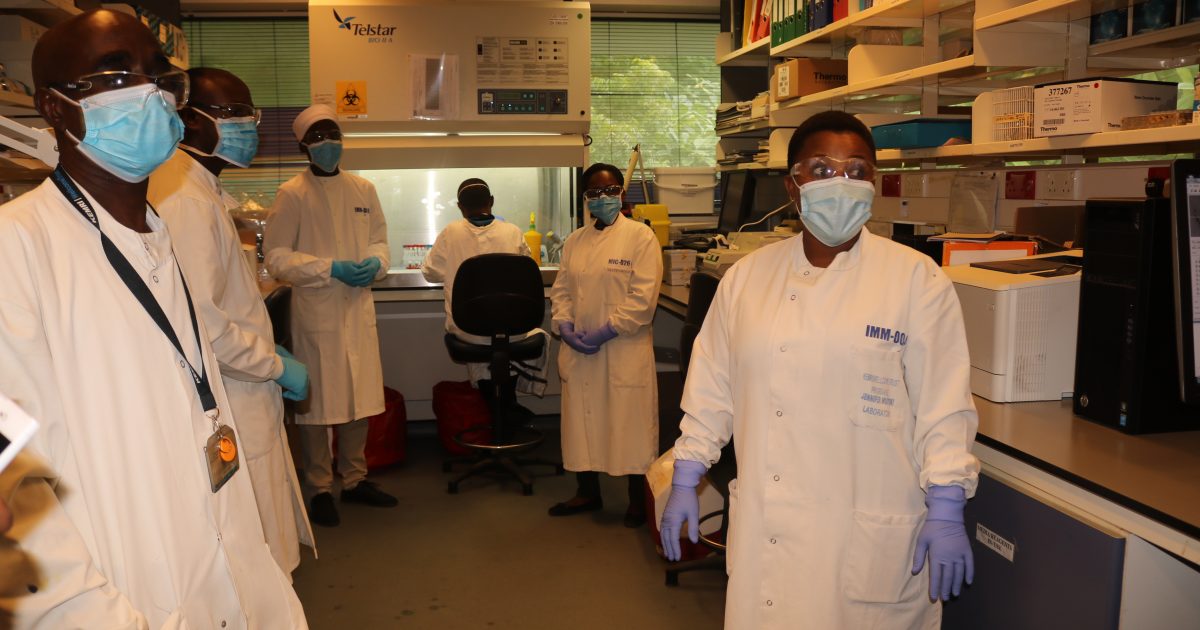

The scientists spoke on Sunday when they conducted journalists around the research facility with the visit designed to support them in their coverage of COVID-19.

Dr. Sam Muchina Kinyanjui, head of training and capacity building said while the virus has upended life across the globe it has only existed for a few months and little is yet known about the coronavirus.

Dr. Kinyanjui said most tests for the new strain of coronavirus involve taking a swab sample for analysis noting that developing reliable tests for the virus is essential to slow its further spread.

He said the virus known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causes coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19).

Dr. Kinyanjui observed that tests usually involve taking a sample from the back of the throat with a cotton swab and then filed staffs send the samples off for testing under very low temperatures.

He said testing for COVID-19 involves inserting a 6-inch long swab (like a long Q-tip) into the cavity between the nose and mouth (nasopharyngeal swab) for several seconds and rotating it several times.

He said the swabbing is then repeated on the other side of the nose to make sure enough material is collected. The swab is then inserted into a cold container and sent to the labs for testing.

“The samples undergo a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test which detects signs of the virus’s genetic material,” he said.

He said currently researchers are studying how the African population is responding to the disease and to fathom how far COVID-19 might spread and what the ultimate consequences might be.

Head of Bioscience department Dr. Isabella Oyier said the institute has been working on basic science research in malaria, arboviruses, HIV, enteric and respiratory viruses and malnutrition studies.

As part of the response to COVID-19, she said the institute is banking on a wealth of experience it has harnessed in undertaking epidemiology programme primarily focusing on arboviruses such as chikungunya, dengue fever and zika viruses.

Dr. Oyier said the research centre receives samples for testing from the coastal counties of Mombasa, Kwale, Kilifi, Taita Taveta, Lamu and Tana River.

“Currently we have tested 10,000 samples and the figure might look small because we have to do control tests because of the stringent quality assurance process that we have to follow” she said.

The department head most people who develop COVID-19 have a relatively mild form of the disease which does not require specialist treatment in dedicated hospitals.

Dr. Oyier said KEMRI is GLP (Good Laboratory Practice) accredited facility that is designed to protect scientific data integrity.

by Hussein Abdullahi

Kilifi based research centre scales up covid-19 testing at the coast