The government has declared drought a national disaster. Some farmers in the country have been prepared for such an eventuality as they try to mitigate the resultant drought effects.

Vast grasslands and other expanses along the Isiolo to Marsabit road abound with camel trains on either side. One wonders the origin and the destination of these beasts of burden as they saunter on their journey, under the watchful eye of their shepherd at the rear.

The camel is an ideal mode of transport for nomadic communities in the arid and semi-arid regions of Kenya. Besides, the animal is domesticated for milk, meat, hair and leather.

Karare Trading Centre is about 25 kilometres to Marsabit. Located on the outskirts of this rural settlement is the 30-acre Korkora camel farm. Angelina Lenawamuro is the proud owner.

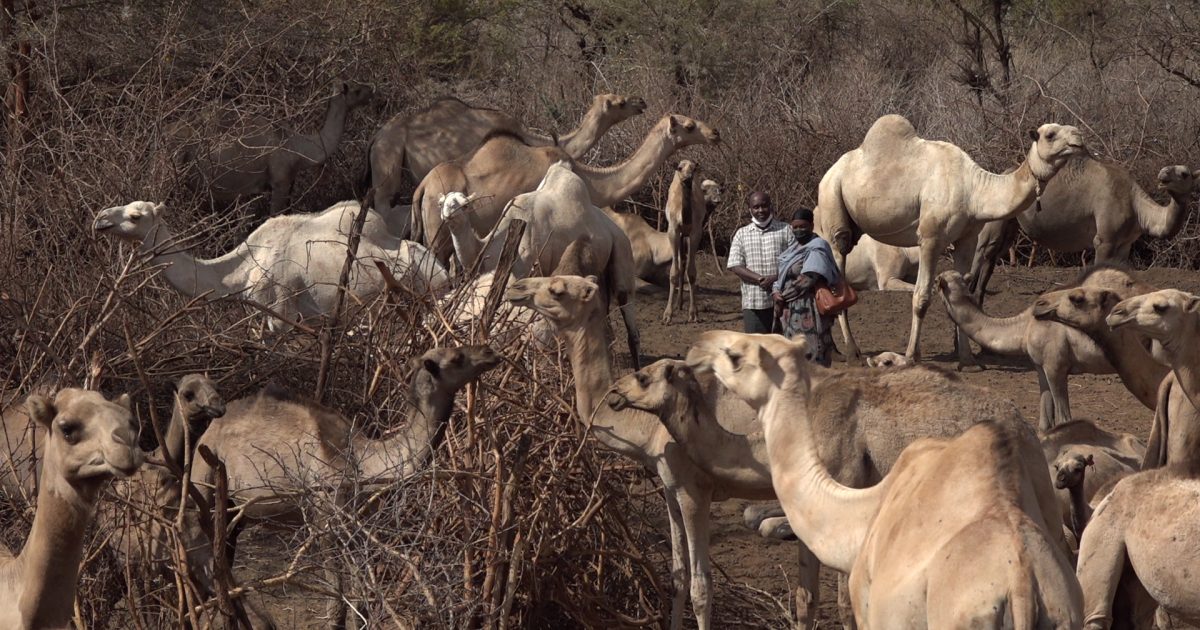

Here on the farm, one can easily think they are in the middle of a camel market from the incessant camel herds’ groans and moans. However, this open-air enclosure of intertwined twigs, serves as a research centre for the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO).

Close to 100 camels are kept here. Clustered separately as families are the Somali, Rendille and Turkana camel breeds. All of them are the one-hump camels known as the dromedary. These animals won’t end up on a dinner plate any time soon. They are specifically reserved for activities related to milk production.

Lenawamuro keeps 40 dairy camels. Twenty of them are Somali and 20 Rendille. “I was impressed by the Somali camel,” she says. “It produces more milk than the Rendille type.”

Milking is done every morning and evening. For each milking session, “One Somali camel produces three litres during drought or four litres when pastures are plenty,” she says, while, “the Rendille produces one-and-a-half litres.”

Milking a camel requires quick reflexes. In fact, two people do it simultaneously. But prior to milking, a calf has to suckle its mother’s teats to stimulate milk flow.

A research technologist at KALRO, Hussein Walaga, says, “A camel allows milk let-down for only two minutes, unlike cattle which do so for five to seven minutes. So milking has to be done very fast.”

As the drought ravages the rangelands and sun scotches pastures, the Somali camel adapts easily to hot climates and therefore has an edge over cattle. Lenawamuro switched to rearing of camels in 2009. “We used to keep cattle,” she says. “But whenever drought set in, most would end up dying.”

The KALRO Director of the Sheep, Goat and Camel Research Institute, in Marsabit, Dr. Kipkemoi Changwony, says, “The Somali breed of camels have been known to grow faster, attain a bigger body weight and are higher producers of milk than the Gabra, Rendille and the Turkana Camels.”

Under the Kenya Climate-Smart Agricultural Project (KCSAP), KALRO is seeking to speed up the multiplication of the Somali camel.

“The gist of the project is to have elite Somali camels breed multiplied so as to have parent stock to distribute later to the farming community,” Dr Changwony said.

KALRO is therefore using Lenawamuro’s farm to research on seed multiplication with a view to dispersing the Somali camel within communities in the arid north.

“We are working towards improving productivity as the environment changes in order to ensure increased wealth creation from farming as a business,” Dr. Changwony says.

Under the KCSAP seed system for the camels, KALRO has established three breeding centres. Forty-five weaners have been acquired for breeding; 15 are in Isiolo. Lenawamuro’s farm and the KALRO Centre in Marsabit also have 15 each. In these centres, one male bull is detailed to serve 14 females for multiplication.

Although the 15 camels on Lenawamuro’s farm are the property of KALRO for research purposes, she’s the beneficiary of the milk they produce.

The farmers at these centres will breed and sell the calves to other farmers near them. The resultant camels will have well adapted to their environments by the time they will have matured.

KALRO has noticed how increasingly difficult and expensive it has become in arid lands to get camels for breeding purposes. Under the seed multiplication system, KALRO hopes to cut down by half, the cost of obtaining camels for breeding.

Lenawamuro started off in the camel business after quitting her job at one NGO. The first camels she bought were proceeds of her savings. She and her husband later pooled resources to buy more camels.

At the time of visiting the farm, there were 42 calves. Lenawamuro controls the population of male camels by selling most of them. For instance, in 2020, she got rid of 18 bulls and bought 15 heifers. “This is because my aim is to increase milk production. The bulls are just for meat.”

One bull, according to Walaga, can serve up to 30-50 camels in a herd. “If you want to change your herd, you don’t go for a female, you go for a bull,” he says. “You’ll have 30-50 calves.”

On the other hand, “When you go for a female, you will wait for two years to get one calf and then wait for another three years for that calf to mature followed by another one year for it to give birth. So within the five years you’ll only get one calf.”

A farmer who buys 50 weaners would stay for five years to get 50 calves. “But if one had one bull, within the five years he’d get 100 calves,” Walaga says.

A mature camel cow costs around Sh70, 000; a young calf, which has just been born goes for around Sh50, 000-60,000. The cost of a bull ranges between Sh65, 000-100,000 depending on the market.

The setbacks Lenawamuro kept experiencing with cattle rearing made her brood over her situation. She decided to try camels.

In 2009 she bought 22 camels, then in 2010 she added 13 and later 15 more. Her herd has kept increasing. She says, “I get about 40-50 calves every year. One or two may die.”

The camel rides on similar height advantage to the giraffe. The camel browses comfortably on the thorny, acacia family trees dotting areas with little rainfall, such as Marsabit. The animal is unperturbed by the thorniest plants in the hot, harsh environment, courtesy of its upper cleft-like lip that allows a thorn to prop up in between the lip while surrounding leaves are snapped up.

Some of the camel milk Lenawamuro sells at her milk bar in Marsabit town originates from her farm. However, other camel keepers sell to her smaller quantities at Sh80 per litre, which she in turn sells at Sh100. She is eager to sell more milk.

“Camel milk has a longer shelf life. You can milk in the morning and use that milk in the evening while it’s still fresh,” Walaga says. “It’s also the best source of vitamin C.”

At Lenawamuro’s shop, customers come intermittently to buy the fresh milk. Whereas some carry it away, a few sip a mug of raw milk right there. The freezer is almost empty because there isn’t enough stock to be preserved.

Dr Changwony acknowledges that there’s a deficit in the production of camel milk in the country and this may not be solved soon.

“Camel milk is the highest priced in the market because of the quantity produced versus the demand,” he says. Having camels that yield higher quantities of milk may cut down on the shortfall.

Lenawamuro hasn’t abandoned cattle. Her attempts to grow her own grass have been futile. “The drought has been quite severe.”

Even though it’s expensive to maintain, the proceeds from the sell of camel milk enable her to buy fodder for her cattle. She buys fodder at Sh400 a bale, from Naromoru, and stores it for use during drought.

The businesswoman has employed three herdsmen to care for her camels. Watering them is laborious. One can easily consume about 100 litres within a few minutes.

At the Korkora farm, camels are watered once a week as opposed to the traditional systems where it’s every 10-14 days. “The once a week production gives the farmer continuous milk supply for one-and-a-half years,” Walaga says.

Watering once a week enables a farmer “to get maximum milk production every day and reach the peak when the calf is four months old and it will take up to 16 months still at its peak production then production will start reducing.”

On a daily basis, Lenawamuro’s business handles between 250-350 litres daily. The camels produce a total of 40 litres while the rest is from other farmers who sell to her in smaller quantities, both camel and cattle milk.

The businesswoman anticipates to increase the size of her farm to 50 acres as her herd of camels grows. “Keeping camels is financially rewarding,” she says.

By William Inganga and Diana Odhiambo