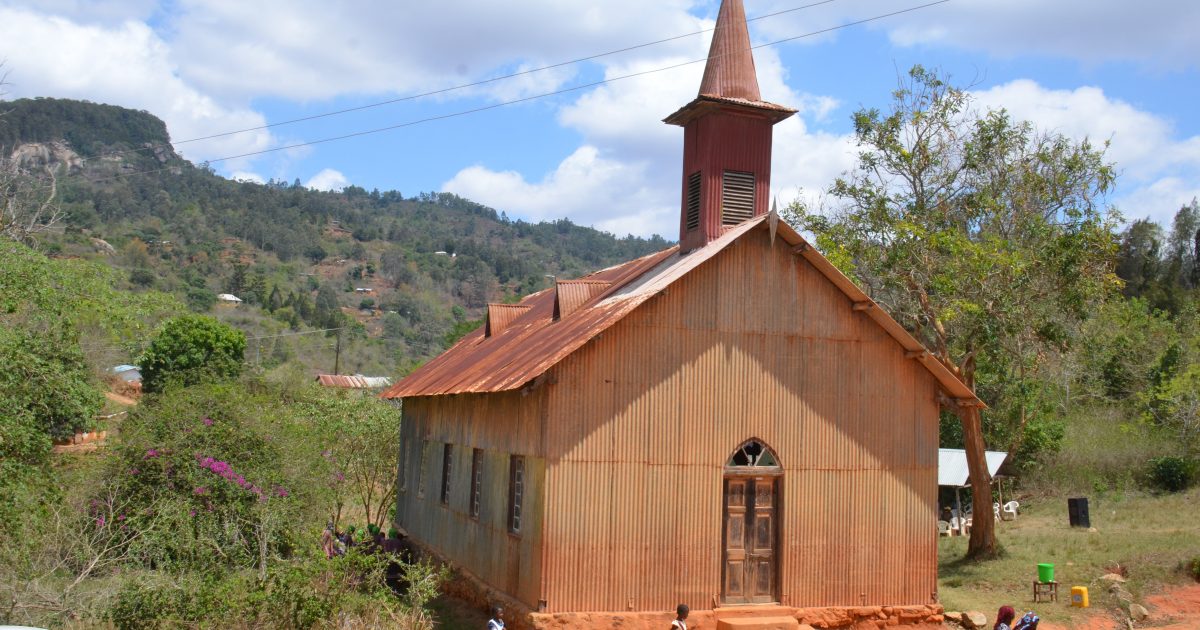

The rust-coated building nestles quietly into the heart of scenic Sagalla Mountains deep in the hinterland of Voi sub-county. It stands tall as it has always done for over a century, a monument of resilience that has defied both time and seasons.

Everything about it reeks of antiquity. The wooden door with the heavy copper deadbolt is crumbly with age. Glass panels are missing from window frames. The towering steeple juts defiantly in the skies like an accusing finger. The walls, made from thick iron sheets, have turned mud-brown from withstanding constant buffeting by the elements over several decades.

Photo by Wagema Mwangi

Mzee Lucas Kisombe, 79, walks around the building gingerly but with apparent familiarity of one who had done the same exercise many times before. He stops in one corner and strokes a brick with a gnarled hand. Etched on the surface of the stone are numbers 1901.

“This is what was written by masons who were repairing the foundation during those years,” he narrates. Mzee Kisombe is an official of the Rev. Wray Museum and a renowned historian of Sagalla community culture.

The dilapidated building he so loves adoringly is Rev. Joseph Wray Memorial Museum. This is a little known pearl that possesses vast cultural and historical significance to the Sagalla Community and to the Anglican Church of Kenya (ACK).

Within it, lies rare antiquated artefacts, cultural items and religious paraphernalia of the Sagalla community from ages long gone.

For 138 years, the museum has survived torrential rainfall and scorching sun. It has towered tall over the rustic land like a lighthouse of remembrance that pays homage to cultural memories and religious traditions that were adopted by their elders in the 1900s. To date, the locals still have a strong attachment to the museum owing to its religious heritage.

It was not always a museum. It started as a religious construction – an Anglican Church of Kenya (ACK) in the 1890’s. Reverend Joseph Wray put up the building as a sanctuary for those who wanted to convert from the existing traditions and adopt the ways of the new religion.

Rev. Wray was one of the earliest missionaries under the Church Missionary Society (CMS). He was the first missionary to establish the first ACK in the hinterland of Kenya. The Sagalla church was the first ACK facility in Kenya’s hinterland.

“The first two churches were set up in Rabai and Kisauni. This was the third in the country and the first away from the Coastal shoreline,” Kisombe said.

After the locals built a new ACK church to accommodate the burgeoning population, the old church house that had served the community faithfully for ages was converted into a museum in 2006.

Inside, the magnificence of the past and bygone ages becomes manifest. Old wooden pews are piled together. There is a large wooden pulpit engraved with elaborate designs standing at the head of the room. The high roofing, the hallowing feeling of timelessness and the still air projects a quaint sense of magisterial poise found in ancient fortresses. A feeling of religiosity still lingers in the walls of the cavernous building. From the sparse furniture to the black-and-white photos adorning the walls, the museum radiates a sense of permanency that is colored by age.

Mzee Kisombe maintains that the museum, small and dusty as it is, is a repository of the disappearing Sagalla culture. Through the carefully preserved artefacts, it offers a window for the present generation to peer into the past and learn of the intricate cultural interaction between a white missionary and local residents.

Amongst the rare pieces still found in the museum includes traditional Sagalla cultural items like three-legged stools, grinding stones, quivers and arrows. There are also diaries, a checkbook, photographs and liturgical items like chalice, baptism register and offertory bowls.

Rev. Wray, an engineer by profession, was also an author. He translated the four gospels into the Sagalla dialect, composed a hymnbook in Sagalla language and wrote an English-Sagalla dictionary.

“He bequeathed us with some writings that can be considered as the foundation of modern Christianity amongst our community. He was also the author of ‘Kenya: Our newest colony’,” says the museum official, adding, “The missionary later went back to England in 1912.”

The museum also has a history of rare cultural transfer. One of the earliest converts to Christianity from Sagalla Community was Mark Mghalu Mwamburi and his compatriot Shedrack Mliwa who would later be sent to Mweiga in Nyeri County to start a church. Rev. Shedrack Mliwa would never return to his land of birth having found a new home in the Central Kenya region.

“His family had come visiting in 2019 because they wanted to know the land of their grandfathers,” said Mzee Kisombe.

However, despite the great significance of Rev. Wray Museum, local residents admit it has been a challenge to manage the facility and prevent it from falling into total ruin.

Mzee Kisombe said that enthusiastic National Museums of Kenya (NMK) officials had in 2017 visited the museum. They were impressed with the documented history and pledged to help support the museum. Years have gone by, but the promise is yet to be fulfilled.

The official said their greatest concern is where to acquire funds to rehabilitate the dilapidated museum walls, roof and floor.

“We are trying our best with what we have but it’s hard. We are fearful of the future of this cultural gem,” he said. He also added that the museum needed visitors who would come to learn about the life of the Sagalla people from over a century ago.

To stay afloat, the museum organizes annual charity walks to raise money for paying the curator and carrying out minimal repairs.

Ms. Rachael Mwakazi, a development expert and a cultural enthusiast, said the county and national government ought to allocate a proper budget for cultural preservation.

She added that rare artifacts and historical sites needed protection and preservation to prevent them from falling into disuse.

“Culture is recognized by the constitution. Preservation of such artefacts should be prioritized,” she advised.

The Sagalla community has asked the government to help in repatriation of documents including books, receipts and photographs that were taken away by the Rev. Wray when he went back to England.

They say that much of the information of the activities of the village was carted off with the missionary and while they maintain good relations with his descendants, his grandchildren lack ability to grasp the significance of those documents to the locals.

“There are so many gaps in the narratives we have from that time. This is why we are asking the government to help us get back those documents,” said Mzee Kisombe.

By Wagema Mwangi