Reading is one of the ways that swing open the door to learning. It’s a favourite pastime for many. Through the printed page, readers travel to places they’ve perhaps been to, or not and may never be. Reading makes us interact with people we’ve seen, met, or not and might never.

For the sighted, reading is largely contingent on what’s perceived through the eyes. However, the uncertainties of living in a world fraught with unexpected events may plunge us into another world; that of pitch darkness.

The adage, “Disability is a club one can join anytime,” is firmly embedded in the minds of education officials in the visual-impairment field. Regardless of such a mishap, reading will continue to demand its rightful due.

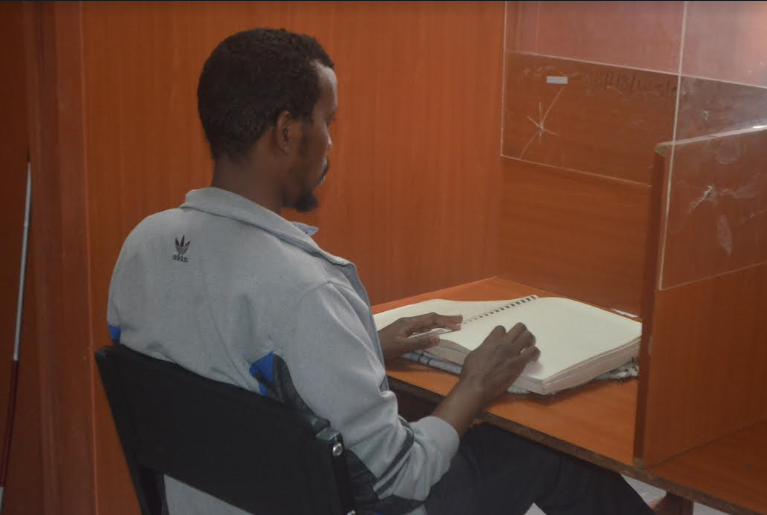

Abdi Fatah is sightless. His insatiable desire to read compels him to regularly navigate his way, with the aid of his cane and guide, to the library at the Kenya Institute for the Blind (KIB) in Nairobi West, to read, albeit with his fingers.

Touch-based reading, Braille, has offered him a glimmer of hope. He continues to enjoy consuming words from the hard pages of embossed literature.

“I was born blind,” he says, as he begins narrating his story. He hails from a rural area in the northeastern part, at the border of Kenya and Somalia.

Prior to his arrival at KIB, he hadn’t acquired formal education in school. He had only been exposed to the Quran taught in Madrassa. He’s now mastered the art of reading Braille.

While living with his uncle in South C, Fatah learned through a relative, that there’s a ‘school’ nearby that caters for visually impaired students. That ‘school’ happened to be KIB.

Fatah neither understood Swahili nor English. Upon his arrival at KIB, he was first taken through mobility orientation. “We were taught how to hold and use the white cane when walking.”

Then, “I was taught Basic English and Swahili,” he says. “This is the institution that taught me how to read and write Braille. I first came here for my training in 2007. It lasted one year.” Unlike millions of other learners, Fatah’s formal education kicked off in Braille.

He joined the Thika Primary School for the Blind in 2008, then proceeded to Thika High School for the Blind. He sat for his Kenya Certificate of Primary and Secondary School Education examinations, conducted in Braille.

At first, “I thought it was impossible but as time went by, I got used to it and in fact I appreciate it,” he says. He qualified for University.

When spotted at his desk in the library at KIB, he’s reading one of two volumes of a book, ‘An enemy of the people.’ “I just picked them randomly,” he says.

“I come here on a daily basis,” he says. He’s borrowed books from this library several times including when he was in primary and secondary schools. The provision has helped him to free himself from the clutches of illiteracy.

The Braille press at this government institution under the oversight of the Ministry of Education, is housed within the Education Resources Department. Production of books in Braille takes place here.

The Deputy Principal of KIB, Lydia Karanja, says, “This may be educational curriculum books for schools such as for the Competency Based Curriculum (CBC) and other curriculum material for different levels like secondary schools and tertiary institutions.”

Fatah doesn’t take for granted what goes into the endless churning out of Braille material for the benefit of the likes of him.

Material used in a school for the blind is often in regular print. The material has to be converted to the embossed type to suit the needs of the visually impaired.

KIB has striven to keep abreast with the changing technological landscape by installing efficient, modern and new Braille machines.

The Head of the press division at KIB, Celine Mutisya, says, “If we receive the books in soft, the work will be easier. But if they are in print, we have to scan them to make soft copies.”

KIB trains transcribers who offer support services to learners in school or tertiary institutions. The Duxbury Braille Translator is the specialised software used to convert soft copy into Braille. Depending on the size of the book and its content, the process may take a few days or even up to a month.

Once a book has been scanned, it is taken to teachers for adaptation. This means making the content accessible to learners with visual impairment.

If there is a diagram in a book to be converted into Braille, “We may not have it as it is. We adapt the diagram and transform it into tactile,” Mutisya says. “Readers would touch, feel and discern what it means.”

After transcription, a copy is produced and taken for proofreading. The proofreaders are teachers by profession. They touch read.

In the proofreading office, a visually-impaired teacher touches with someone who is sighted. The sighted person has the print while the touch reader, the Braille copy respectively. The pair reads word for word to ensure that what’s in the print copy is the same as what’s in the Braille book.

Morris Maganju is a sightless touch reading proofreader, while Susan Kazilika, a sighted one, at KIB. Maganju scans the raised dots with the tips of his fingers, audibly pronouncing each word and punctuation. Kazilika follows along with sharp eyes, keen to verify. At the end of one sentence, Maganju says, “Exclamation mark!”

There’s a mismatch. “This one is full stop,” says Kazilika. The error is marked with a pen on the Braille page, slated for correction.

Once the proofreaders certify that the book is accurate, and that the adaptation is suitable for the learner with visual impairment, mass production follows.

The documents are sent electronically to an embosser. This is the machine that produces the tactile dots, referred to as Braille.

The final copy is the hard copy Braille. If there are diagrams made to tactile, someone crosschecks where to place them in the book.

“We don’t insert the original copy,” Mutisya says. “We insert a copy that has been thermoformed. Thermoforming is like photocopying.”

After insertion, these are taken for binding. Quality check is next. “We need to confirm if the Braille book is the same as what we received originally,” Mutisya says.

Fatah has scanned, with the tips of his fingers, innumerable copies of such publications. Schools and tertiary institutions offering special needs education across the country are dependent on Braille. As a result, inclusivity in education is being fostered for the visually impaired are presented with opportunities to learn.

This is in line with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 which aims to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.”

To demonstrate how vital a role KIB plays, Karanja cites the example of a science teacher who loses sight. The mind of such a teacher would go blank. “KIB serves as a rehabilitation centre in the country, for such newly blinded persons,” she says.

“We have learners who lose sight when they are in primary or secondary schools or even at the university,” says Karanja. “We rehabilitate them by empowering them with reading skills in braille for English, Swahili and Mathematics.”

Thereafter, they are sent to the Teachers Service Commission (TSC) for posting either back to their station or elsewhere.

KIB ensures that new clients receive guidance and counseling. This enables them to come to terms with their new situation rather than sink in denial following the traumatic experience of losing sight.

KIB also organises psychosocial support. “Once every year, we visit the families of those who have lost sight. We talk to them about the need to offer support to the affected,” Karanja says. “We assure them that after rehabilitation, the person would be independent and their worry may be short-lived.”

Learners going to KIB commute. Like Fatah, some may be from the furthest corners of the country. Hostels in the neighbourhoods of KIB might be too expensive.

“We are building our own hostel,” Karanja says, pointing at the new block. “This hostel is a game changer for this institute and it will be ready for use in 2023. We are going to rehabilitate more learners and this is good for the country.”

“When we do outreach programmes we come across persons who lost sight but are locked in houses,” Karanja says.

Fatah finds the stigmatisation tendency perturbing. It further disturbs him that some parents despair, imagining that their children’s blindness portends a bleak future due to their condition.

“I urge such parents to free their children and take them to relevant schools to learn. This will enable them to do almost anything for themselves,” he says. To the visually impaired, his message is, “Work hard to achieve your desires.”

Braille is the universal written communication medium of the blind. It has brought a degree of light to Fatah who would be confined in a prison of darkness.

“I just completed a course for special youth education,” he says optimistically. “I’m interested in being one of the Special Needs teachers in Kenya.”

By William Inganga